Discussing climate change with the next generation

by Nicole Castañeda

Summer Program Intern

As the summer intern at the Stone Living Lab, I’ve spent much of my time as an educator, which was a little outside my comfort zone. I have been a summer camp counselor, but this is a whole different ball game, one without a set curriculum and schedule but with the leeway to ensure that education doesn’t feel like a chore or something that can be done ‘wrong.’

The pop-up events we do are entirely optional for the children; they don’t have to be there, so if they come up to us, there’s no need to fight for their attention. This allows us to have conversations instead of lecturing at them. We can talk about the topics we’re trying to teach and their experiences and make these topics more personal for them.

The kids we work with vary in age, but a typical range is from around four to eight years old, so elementary school-aged and a tad younger. I love working with children; they’re at an age when they’re more than happy to share their opinions and experiences, and getting to nurture them is a joy. We can educate them while reinforcing that science and learning are fun and that there’s no such thing as a genuinely incorrect answer as long as they’re trying and other life lessons that I hope some carry with them.

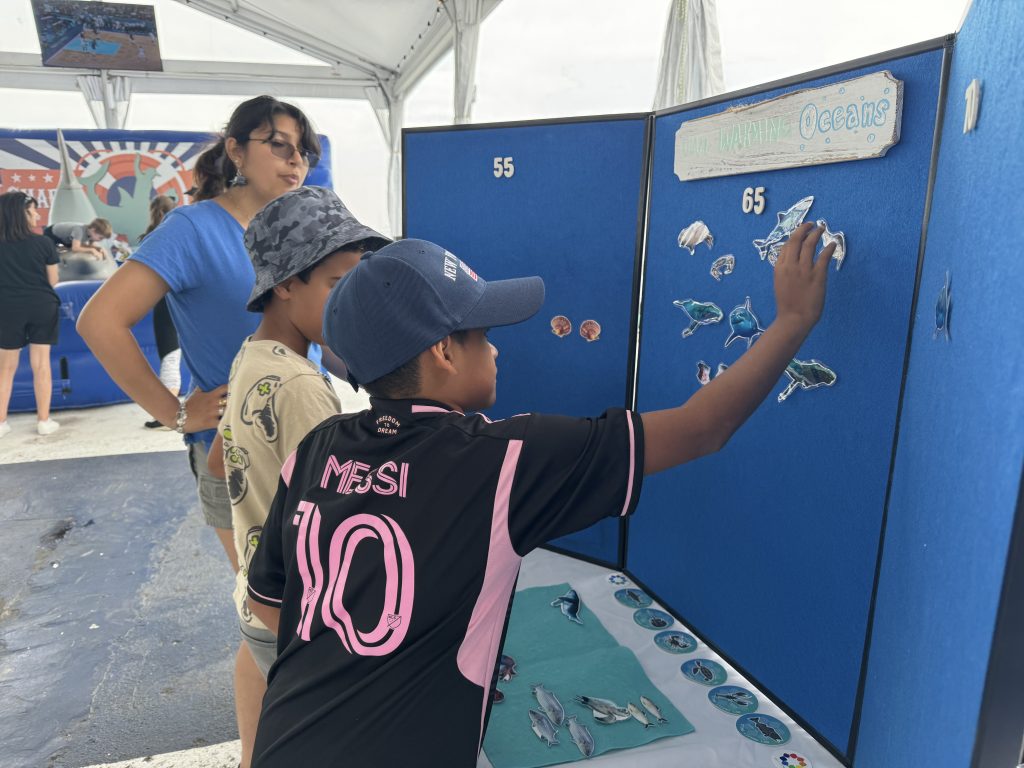

Exploring how warming ocean temperatures might affect native marine species.

This part of my job aims to educate them about challenging issues without bursting their bubble. Words like climate change, ocean acidification, and global warming are pretty scary for a little kid, so it’s essential to find a balance between getting the point across and not skewing their perception of the world.

Keeping up with children is a challenge; they throw curveballs at you in ways you couldn’t even fathom, and that’s the fun of it! Most children are happy to share their unique perspectives, and it not only helps you notice any gaps in their climate education that we can help remediate, but it also gives so much insight into how they see their world. Balancing interacting with them with the same energy they give so they don’t feel discouraged and trying to gauge their interest in what we’re trying to teach, along with their knowledge level, is a tricky mix. Still, once you get it, you can see these kids make their own conclusions, bring their own passions in, and become more connected to the world around them, which is always worth the effort.

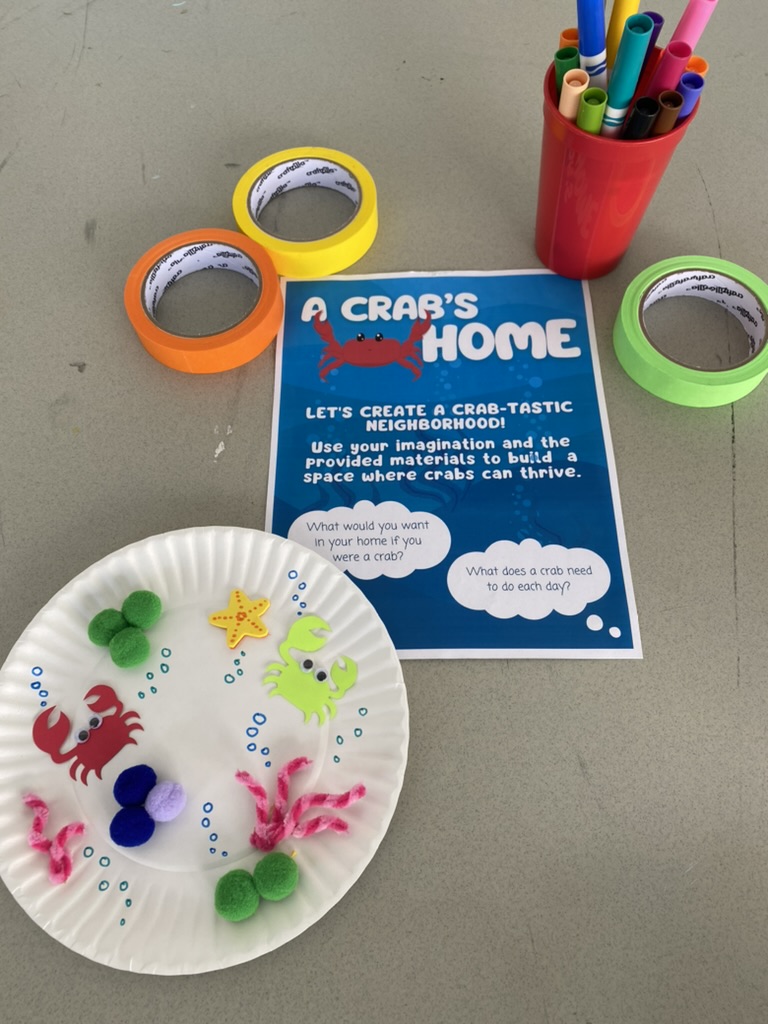

In collaboration with Boston Children’s Museum, our “A Crab’s Home” activity lets participants imagine ways to create habitats for our marine neighbors.

Educating them on topics like climate change has to be done very carefully: you’re trying to foster a positive connection with their environment, a love for the planet they live on, and a respect for the native environments, peoples, animals, and plants from where they live. It’s a difficult thing, discussing past mistakes, broken promises, and traumas of the land.

Having grown up in the American South, I know how important it is to recognize harsh truths about the past. It’s more challenging to deny history because the physical evidence can surround you. Yet, being more subtle and long-term, climate change allows for a disconnect between seeing and believing. That makes it vital to accept hard truths about the present and the worrying potential for the future.

Climate change manifests itself in many different ways; because of that, it’s hard to create a definition or show an example that resonates with everyone about their home area. To people back in my home state of Tennessee, climate change sometimes manifests in more snow, but up here, it means that there’s less snow. We know about classic examples like the polar ice caps, but we’re so far removed from them, so few of us have even seen them, that it’s simple to let it become ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ Many of the activities we do at pop-ups, like our climate carts, aim to bring the topic home and show you hands-on what could happen and, quite literally, give you the tools and materials to try and stop it. It’s a lot more personal when you’re stacking sponges to save a beach town or rearranging blocks that represent buildings to ensure they don’t flood, and it lets them have fun with it, too. There are no consequences in these activities; they can try again as many times as they need, and they gain an even better understanding every time.

The outreach we do at the lab doesn’t completely combat the lack of climate change education. No, it’s difficult to tell a kid everything you think they need to know about such a multifaceted subject within 10 minutes. No, we can’t teach them expert vocabulary, data analysis, or the entire issue of activism and making significant change. But we do start the ball rolling. Learning about something you’re familiar with is easier, even on a more basic level. We make sure kids have that baseline understanding and love of their environment, and hopefully, we help change the way they view education as well, making it into something fun instead of stressful. It’s unnecessary to scare kids with the idea of ocean acidification, acid rain, increasingly severe weather, and other wild changes. You can just introduce them to the world around them, make them think, and help foster a love for where they live because if they love it, they’ll want to protect it, and when the time comes, they’ll know what to do.

Nicole was the Lab’s 2024 Summer Programs Intern. She is now back at University of Rhode Islands studying Marine Biology and Underwater Archaeology. She will be greatly missed!

Nicole celebrating her first-ever sighting of a wild sea star in Boston Harbor!