Field Observations: Real-Time Data from the January 13 Storm & Flooding in Boston

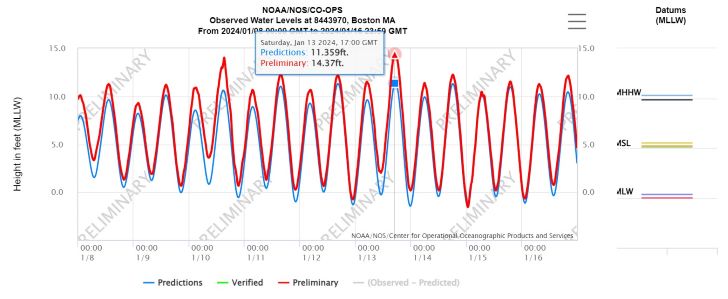

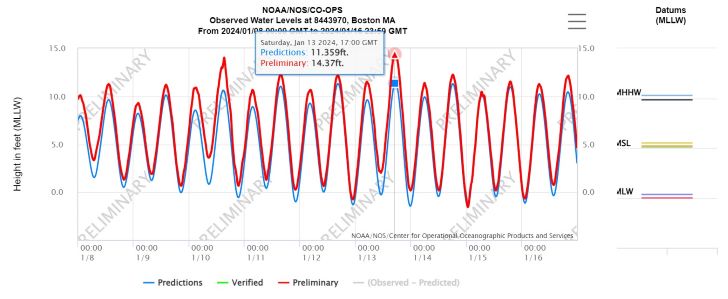

For the second time in less than one week, Boston experienced a significant storm event that caused flooding throughout the city on January 13, 2024. During this event, the late morning high tide was the fourth highest water level ever recorded at the Boston NOAA tide gauge.

Flood barriers are deployed at Aquarium Station on the Blue Line on January 13, 2024 (Photo by David Weaver)

Similar to the recent storm on January 10, 2024, the flooding at Long Wharf in Downtown Boston, East Pier Drive in East Boston, and other locations was captured on video by journalists and residents and shared on the news and social media.

Meanwhile, our team at the Stone Living Lab was again gathering data via instrumentation that we have deployed as part of our Real-Time Monitoring in Boston Harbor project, launched this fall in collaboration with Woods Hole Group and the City of Boston. Collecting high-quality, continuous metocean time series data helps the Lab and municipal partners like the City of Boston evaluate normal, changing climate, and storm conditions in Boston Harbor, which helps inform adaptation and resilience planning.

Please see below for a short summary of data readings and observations.

A flooded Harborwalk between India Wharf & Central Wharf on January 13, 2024 (Photo by David Weaver)

At the Boston NOAA Tide Gauge, high tide peaked at 11:48 am at 14.41 feet Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW), which was over 3 feet higher and half an hour earlier than the predicted high tide level.

This surge referenced above was also observed at our Hohonu overland flood stations throughout Boston (all in inundation depth, in feet above the ground surface).

Flooding outside of the New England Aquarium on Central Wharf in Downtown Boston (Photo by David Weaver)

Our Rainsford Island station recorded sustained wind speeds reaching 28 MPH, with gusts up to 38 MPH peaking on January 13 at 6am.

Our Gallops Island tide gauge recorded flood tide elevation of 8.5 feet NAVD88 at 12 pm on January 13. This was approximately 0.8 feet higher than the high tide recorded on January 10.

Flooding at a picnic area outside the New England Aquarium on Central Wharf in Downtown Boston (Photo by David Weaver)

This project – launched in the fall of 2023 in partnership with Woods Hole Group and the City of Boston – provides real-time monitoring of waves, water level, and meteorological parameters in and along Boston Harbor. The project is the next phase of work that the Lab has conducted since 2021, and provides a continuous time series of metocean data to evaluate normal conditions, changing climate, and storm conditions in Boston Harbor. All systems are real-time, and as such, will provide preliminary data to the web that can be viewed by the public as well as our researchers.