Snails, mussels and seaweed: Boston project aims to bring life to barren seawalls | WBUR

The Lab’s pilot Living Seawalls project, Managing Director Joe Christo, and UMass Boston researcher Jarrett Byrnes are featured by WBUR, highlighting how new engineering designs can help “green the gray” along Boston’s shoreline.

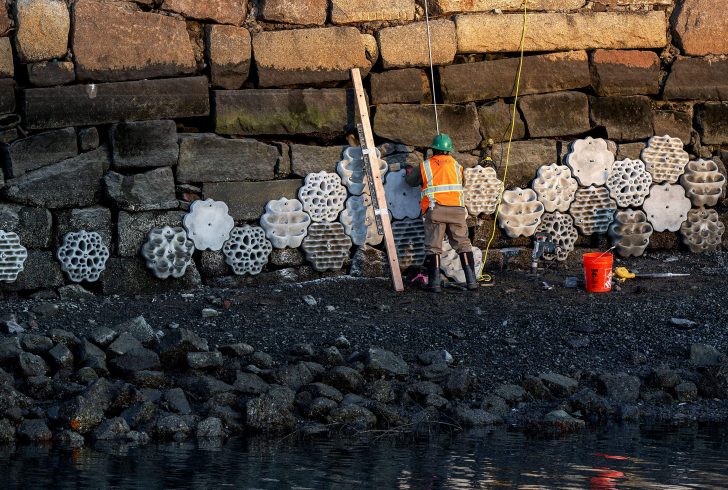

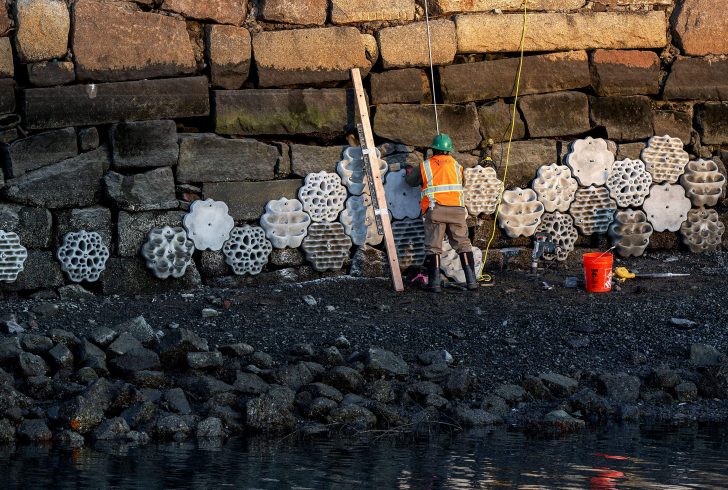

Work underway at the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

The Condor Street Urban Wild is a grassy oasis in East Boston, with park benches, walking paths and plenty of open sky. The park borders Chelsea Creek, a waterway far more urban than wild. At low tide it’s possible to scramble down to the rocky beach, which is shared by seagulls and shards of broken glass.

A pilot project from the Stone Living Lab at the University of Massachusetts Boston aims to make this stretch of urban beach more friendly for marine life by turning part of a seawall into a haven for shellfish and seaweed.

Hugo Urbina and Jeremy Simon, of SumCo Eco-Contracting, fix a panel into the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

“It’s kind of an ecological wasteland, right?,” said Jarret Byrnes, appraising the nearby seawall with an appraising eye. Byrnes is an associate professor of biology at UMass Boston.

“You can see there’s some barnacles, there’s some green algae, but most of what you see on this seawall is just big, flat concrete and stone blocks,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is change the story.”

The story is a common one in Massachusetts. The state has more than 1,500 miles of coastline —Boston alone has about 47 — and many communities rely on stone or concrete seawalls for protection from storms and floods, especially as risk increases with climate change. These flat walls often make poor homes for marine life and can decimate coastal ecosystems.

Jarrett Byrnes, a professor in the Biology department at University of Massachusetts, Boston, near the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

Ideally, natural ecosystems that offer both flood control and habitat — like wetlands and salt marshes — would have been left in place. In some cases these can be restored.

But there’s another possible solution. In Chelsea Creek, workers are re-engineering the lifeless stone wall into a “Living Seawall,” by bolting 120 concrete panels onto the granite blocks. Each 40-pound, 2-foot-wide panel resembles a giant snowflake, covered with nooks and grooves. They’ll be underwater at high tide, providing a home for seaweed and shellfish.

Hugo Urbina, of SumCo Eco-Contracting, lifts a panel into the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

“Living Seawalls are a way that we can have a real win-win when it comes to protection from sea level rise and storm surge,” Byrnes said. ” We can both implement protection for people, and we can also create these beautiful natural habitats that are going to allow the shoreline to flourish.”

Stone Living Lab Managing Director Joe Christo said the project kicked off a over a year ago, with a call from Buckingham Palace.

The Living Seawalls technology was a 2021 finalist for the Earthshot Prize, Prince William’s international climate solution contest. The Australian creators wanted a partner to bring their tech to North America. Now, their first two sites on this continent are in East Boston and the Seaport.

Joe Christo, the Chief Resilience Officer for Boston Harbor Now, near the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

“Both of these sites are prototypes,” said Christo. His group plans to monitor the installations over the coming year and may add other sites around Boston.

The panels will not harm the seawalls, Christo said, and could add benefits for humans, too — a more attractive intertidal zone, possibly cleaner water, and a restored ecosystem that connects an industrial inlet to the living ocean.

“These living seawalls are a way of making gray infrastructure more green,” he said.

A sea snail makes its way up a recently installed section of the living seawall. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

The pilot project cost about $400,000, or about $400 per square foot, according to Christo. The cost includes site selection, design, fabrication, installation, project management, permitting, research and monitoring. The Stone Living Lab is picking up the tab, and partnering with organizations like the Museum of Science and the Children’s Museum for outreach and education.

Byrnes and his students at UMass will study the installations for signs of life over the next year, to see which plants and animals show up, and which of the five panel types allow marine organisms to flourish. The project appears promising so far. Some of the panels were sheltering mussels and snails only a few days after being installed.

“It’s pretty exciting,” said Byrnes, oooing and aahhing with delight as he searched the panels for tiny creatures. “It’s just like a kid in a candy store, to go out and just see every day, who’s popped in, who’s fallen in, who’s living there.”

SumCo Eco-Contracting staff fix panels into the new living seawall at the Condor Street Urban Wild in East Boston. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)